Let's Talk About the Weather

In this episode of Pirates Only, I dive into the world of innovative weather technology with three incredible founders: Alex Levy from Atmo, Austin Tindle from Sorcerer, and Andrew Song from Make Sunsets.

Here are some of the topics we cover, TLDR style!

AI Meets Meteorology

Atmo is revolutionizing weather forecasting by leveraging cutting-edge AI, similar to ChatGPT but for atmospheric science, delivering unprecedented accuracy to governments and organizations around the world.

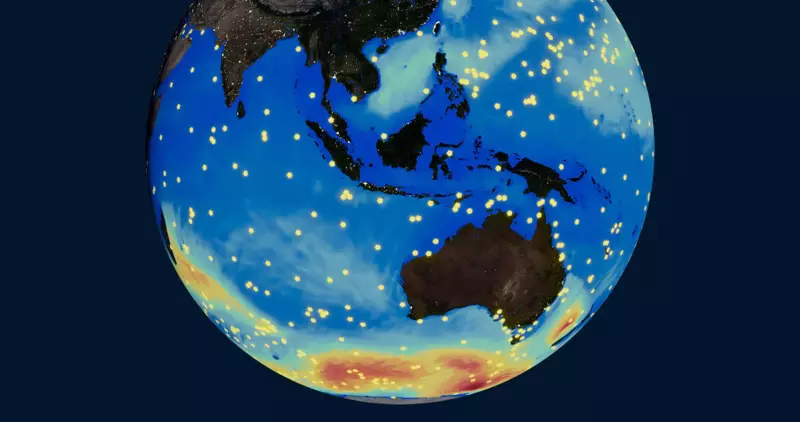

Oceanic Data Revolution

Sourcerer's innovative long-duration balloons are gathering vital atmospheric data over oceans, an area previously lacking critical information, fundamentally transforming our predictive capabilities.

Cooling the Planet, Volcano-Style

Make Sunsets is pioneering solar geoengineering by releasing reflective sulfur dioxide clouds into the stratosphere, safely mimicking volcanic cooling to combat global warming.

Strategic Alliances for Impact

Atmo and Sourcerer’s just-announced partnership aims to deploy balloons for hurricane forecasting, potentially saving countless lives and billions in climate-related damage.

Geoengineering Ethics

Make Sunsets openly addresses the ethical and environmental considerations surrounding geoengineering, emphasizing cautious optimism and responsible innovation.

Climate Control for the Earth

This emerging synergy among tech startups is creating a holistic approach to climate control, highlighting the human potential to proactively manage Earth’s climate.

Bring your sun screen - this episode is hot.

00:00 Introduction to Innovative Weather Solutions

01:59 Deep Dive into Atmo's AI Weather Forecasting

05:00 Exploring Solar Geoengineering with Make Sunsets

07:47 The Role of Balloons in Weather Data Collection

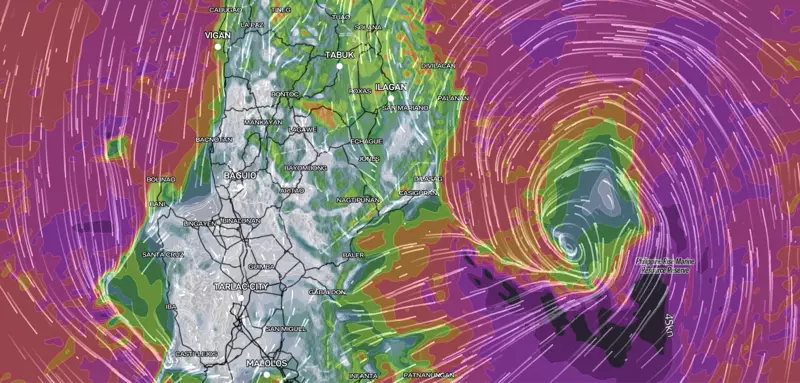

09:37 Impact of Improved Weather Forecasting in the Philippines

12:17 The Importance of Data in Extreme Weather Events

15:15 Partnerships for Enhanced Weather Prediction

18:18 The Future of Weather Forecasting and Climate Change

21:02 Conclusion and Future Directions

29:24 Advancements in Weather Forecasting

31:18 The Role of AI in Meteorology

32:25 Partnerships and Future Directions

34:09 Innovations in Climate Intervention

47:31 Addressing Concerns in Geoengineering

53:31 The Future of Weather Technology

Mat Vogels (00:13)

Well, we'll just get right into it. Let's start with some introductions. Alex, let's have you start. Give a brief introduction of who you are, what you're building, a little bit about your company, and then we'll dive in a little bit deeper later.

alexjlevy (00:25)

Redon, great to meet you. Great to be on Pirates Only. ⁓ Atmo is AI for the atmosphere. So starting in 2020, we came out with the first deep learning neural networks that could predict the weather. And so just the same way that you've got chat GPT predicting the next word or phrase or paragraph of text, we invented large scale transformers for weather information. And we've used that to build some of the most detailed and accurate weather forecasts.

That are in operation today and we do that for amazing people like the US Department of Defense, the Republic of the Philippines, ⁓ all the space launch sites in America and many others and we've been operating that right here from San Francisco, California.

Mat Vogels (01:04)

That's awesome. We'll dive back into some of the details there, especially how you started, why you started, but let's keep going around for introductions. Austin, how about you give us a little intro.

Austin Tindle (01:15)

Yeah, thanks for having me on. So I'm Austin, CEO of Sourcer. Sourcer, started just last year, ⁓ April 2024. And we're building weather balloons that collect a thousand times more data than the traditional infrastructure that typically collects this type of data. And yeah, we recently announced our $4 million seed round. yeah, ⁓ we have a small team here in San Francisco doing ⁓ logic weather balloons.

Mat Vogels (01:38)

Congrats.

Love it. Thank you. Andrew, last but certainly not least, tell us a little about Make Sunsets.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (01:50)

Thank you for having me on. My name is Andrew Song. I'm the co-founder of Make Sunsets. We started back in October 2022. And what we do is we launch reflective clouds near the ozone layer to cool Earth. That's a type of thing called solar geoengineering. The world is getting too hot and we think we could cool it down. And so we have roughly 900 customers. Probably the most famous customer you probably know about is Palmer Lucky. He gave us a few dollars to cool things down.

But it's very pirate-esque. We're the first company in the world to try to do this. It's been in academia since the 1970s. Over 2,000 academic papers have been written about this. It's been very well modeled. ⁓ But no one's actually tried to do it. And so we're the first to try.

alexjlevy (02:30)

Thanks.

Mat Vogels (02:32)

That's amazing. Andrew, let's keep it with you. Could you dive a little bit deeper into what specifically is being done in doing that? What is the technology look like? ⁓ And then maybe tie at the end of that. Why has this not been something that's been done before? Why are you the first in doing this?

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (02:48)

Yeah, so

alexjlevy (02:48)

you

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (02:49)

what we do specifically is send sulfur dioxide

into the stratosphere. So the stratosphere is ⁓ where we deploy is roughly 20 kilometers above or about 66,000 feet. So this is double the height of where commercial airliners generally fly. And so what we're essentially doing is mimicking what volcanoes have been doing for millions of years, specifically stratovolcanoes. So ⁓ the most ones that were recent history that actually cooled the planet was Mount in 1991. So ⁓ Alex has talked about the

The government of Philippines, one of the most famous volcanoes there is Mount Pinatubo, injected roughly about 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. It cooled the planet by 0.5 degrees Celsius. And then there was actually another recent volcano called Hunga Tonga in 2022. I'm not making up that name. It's actually a real volcano. It's off the coast of New Zealand and it injected roughly around 400,000 to 700,000 tons of sulfur dioxide. It cooled the planet by 0.1 degrees Celsius in the southern hemisphere. And it lasted for roughly about a year.

And so ⁓ essentially we're trying to mimic that. ⁓ And the reason why we're doing it now versus, hey, a decade ago is because ⁓ there's this magic number that a lot of scientists as well as like the IPCC, which is like a governing body that like tries to track the weather as well as global temperatures said we're about to cross this threshold called 1.5 C. So 1.5 degrees Celsius. ⁓ And scientists have said, hey, currently we're doing a rate of warming about

1.25, or I'm sorry, 0.25 degrees Celsius per decade. And so this rate of warming is starting to become dangerous. Right now, the US, a lot of the US is experiencing a heat wave. And as global temperatures increase, more of these heat waves will happen and more energy will be put into the system, causing more of these catastrophic climate events. Specifically, I think there was a report Bloomberg had said that just in the past 12 months,

stopping in May 1st, about a trillion dollars worth of climate damages have occurred in the past 12 months. And so, and this is directly caused by warming. And so we're trying to figure out how to cool things down. And we know that stratospheric aerosol injection based off of nature, as well as ⁓ actually the ground level emissions of SO2 that are currently being emitted is cooling down the planet. So ⁓ we're just trying to do it better essentially.

Mat Vogels (05:10)

Why haven't why isn't this been to why is this more readily done? isn't this not the norm? And there are some more companies doing this today.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (05:18)

I mean, that's a great question. There's been attempts before. ⁓ Specifically, there was this Harvard team called Scopex. It was funded by Bill Gates. $20 million went in. They tried to do it, ⁓ but couldn't launch. They were actually blocked by a bunch of NIMBYs, essentially, saying, don't do this in my backyard. ⁓ And it was more of an academic effort. Therefore, there wasn't really a commercial reason to do it, more of research. But even then, it was considered controversial.

Austin Tindle (05:35)

Thank

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (05:46)

⁓ back when they were trying to do it. I think that was the big thing that kind of gave a lot of people pause. ⁓ I guess the real thing is it is the controversy. Instead of like a lot of people say around sustainability or climate tech, instead of ⁓ removing something from the atmosphere, AKA greenhouse gases, we're actually adding something to it. And so that's a fairly foreign thing to approach a problem. Instead of taking away, you were adding something to the system.

⁓ And so people are not so happy about that sometimes when they first take a look at it.

Austin Tindle (06:19)

Yeah, and just a question that I've been super curious about for a while now. Andrew, is there any regulatory body that is overseeing this? Is the EPA looking at what you guys are doing, or IKO internationally, or something like that?

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (06:38)

Absolutely, absolutely. Yeah, so we actually had a tweet from Lee Zeldin, the head of the EPA, back in May 15th, so about a couple of months ago, saying, hey, what are you guys doing? So we had no prior knowledge that he was going to actually blast us on Twitter and then release this press release saying, what are you guys doing? But since no one has done this before, essentially, they wanted to ask questions. And so we actually hired some former general counsels of the EPA to respond.

Austin Tindle (06:45)

Thanks

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (07:06)

Essentially say, hey, you guys don't regulate this space. We operate in the stratosphere. EPA mainly has jurisdiction in the troposphere. ⁓ And so ⁓ I can share that link later if you guys want. It's about four pages, so fairly short. And then in terms of regulations, ⁓ the ones ⁓ that you have to report is under NOAA. So there's this thing called the Weather Modification Act of 1976.

And that falls under cloud seeding as well as solar radiation management, so solar geoengineering. And so we report yearly ⁓ to NOAA to say, hey, this is how much sulfate aerosols we've put into the stratosphere.

alexjlevy (07:43)

you

Yeah,

so Andrew, we do have this in common in the Philippines though, which is, you know, I feel like both of us have roads that lead us to that country. Philippines has been the number one natural case study of solar geoengineering that's occurred in the last, you know, 50, 100 years that we know of.

Mat Vogels (08:06)

Why is that by the way, before you go in there, what makes them so unique? Okay.

alexjlevy (08:09)

Mount Pinatubo, the largest

⁓ volcanic mass ejection of sulfur dioxide. But what leads atmo there is they also simultaneously the country that gets the most typhoons dead on in their territory of any country in the world. So it seems like every extreme weather event on either side of the equation, all roads lead to Manila.

Mat Vogels (08:31)

any particular reason besides it can't just be that volcanic eruption or is it or what's the what are the biggest reasons for that?

alexjlevy (08:37)

Well, we're talking about two categories here. One is the fact that there is this volcanically active island chain, 7,600 islands. I was actually with the US ambassador to the Philippines a few days ago, and I said, oh yeah, country of 110 million people. And she said, actually, you got updated. They're adding 3 million a year. It's 118 million people now. So it's a really rapidly growing country. But it happens to be both in the belt of volcanic activity, that sort of Pacific rim of fire, but in addition,

Mat Vogels (08:42)

Exactly.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (09:03)

The Ring of Fire.

alexjlevy (09:06)

is directly in the target zone for the sort of Typhoon Alley of Southeast Asia. So the Philippines sort of receives it on both of those levels. And that's why both of us have something interesting to find in that country. Yeah, and just to sort of elaborate, Atmo just completed a new national weather model for the Philippines, all end-to-end with AI. And so we went to them starting about a year and a half ago. We asked them to write their dream specification. If you were to upgrade your national weather service, what would be your absolute?

dream to do. And they gave us this incredibly high-end spec, 10 times the spatial resolution, twice the duration, 50 % reduction in error. And we gulped hard coming back and figuring out how we're going to do this, ultimately delivered it over a series of versions over the last year. And that just culminated in the one-year anniversary. We had a big party here in San Francisco. We had folks from the Philippines consulate. And we announced that of all the models that

were available in this last typhoon season, this new deep learning model by Atmo for the Philippines was by far the best performing while being the most detailed and the furthest into the future. So, you know, it's finally reaching a point where there's, I think, consensus emerging that AI for atmospheric science is going to be the predominant method going forward for the biggest and best forecasting systems in

Mat Vogels (10:29)

Could you maybe double down on the, what does that mean for them as far as like live save? Like what is the benefit obviously of being able to predict the weather that much better in a country like that where they do have these severe weather patterns? And could you maybe dive into some of the benefits that that has there?

alexjlevy (10:46)

Yeah, as we go into year two of the program with them, the types of direct analyses of the availability of these better forecasts translating into human outcomes is going to be one of the forms of analysis. So we're going to get better and better numbers on that specifically. But as a practical matter, there's a huge correlation between whether your forecasts are good and timely and far in advance and precise and whether people can do something about it. So classically, when it comes to things like typhoons,

⁓ You know, you have to decide where you're going to send first responders. So, you know, the Philippines is an enormous responder force, hundreds of thousands of people that sometimes mobilize jointly between the civil and military services. ⁓ And if you send them to the wrong island in a chain of thousands of islands or the wrong ⁓ zone around Manila, you basically render ⁓ useless what you're doing or make it highly, highly effective if it's targeted well to where flooding will occur and extreme wind and so forth.

⁓ So, you know, we expect to have a really significant effect on public safety, the quantification of which will come in time. But I think anecdotally folks can appreciate even in the US context, if you think about ⁓ the flooding in the Appalachia region with, you know, the sort of unexpected hurricane reaching far inland there. Again, that's a case where most of the damage accrued, where there wasn't anything that was done proactively or very limited steps done proactively.

Austin Tindle (11:43)

you

alexjlevy (12:11)

So, generally the theory is if you're gonna get kicked in the ass, it helps to know precisely when and where and how you're gonna get kicked in the ass.

Austin Tindle (12:18)

also kind of a good case study for why the type of data that we're collecting is super important. Typically typhoons are forming far off the coast in the Pacific where there is no ground infrastructure. Really, you just have satellite data out there. Satellite data comes with a huge number of limitations.

There's no sensing infrastructure that is collecting data at the source. And it's been shown that that's the type of data that really is the gold standard, the highest impact ⁓ per unit of data that you can feed into both the traditional numerical weather models, but also in this age of ML weather forecasting where costs to actually run due inference have come down by thousands to tens of thousands of times.

It's so much cheaper now that you can throw more data at some of these models. But the data just doesn't exist. So only about 15 % of Earth's atmosphere is actually covered with some of this high quality in situ data that you traditionally collect with single use latex weather balloons and that we're collecting with kind of balloons that fly for months at a time and can collect 1,000 profiles where a traditional system would collect one.

But yeah, the oceans, a lot of weather happens over the oceans and it's usually becomes pretty destructive pretty quickly.

alexjlevy (13:39)

Totally.

This is why we got so excited about Sorcerer when they came on our radar going through YC. we're, know, Atmos is a YC company, Sorcerer is a YC company. And I remember, actually Austin, I don't know if we've talked about this in a while, but we did one of your early balloon lunches in San Francisco together.

Mat Vogels (13:43)

Well, yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (13:58)

Nice.

Austin Tindle (13:58)

Yeah,

think ⁓ launch number eight or something was actually what you were there for.

alexjlevy (14:02)

So cool.

Yeah, in fact, know, Matt, we'll have to get you, if we can, a copy of the photo or video because ⁓ as the sorcerer team was putting up the balloon, I think somebody handed me a camera. It might even have been my phone. I can't recall. And I was sort of videographing this and like running down, I think it was maybe in the beach near the Presidio, Christie Field type area. And so I was sort of running through the sand trying to capture you guys, you know, get this thing up. It had a crazy path. It was an extremely windy day.

Austin Tindle (14:14)

Yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (14:22)

Nice.

Austin Tindle (14:29)

Yeah, we launched in like 20 knots of wind. that was definitely the most, like the highest wind launch that we'd done at that point. And so we were just, we were like, OK, we got to get this thing off. Or we invited Alex from APNO to come see it. So we got to make it happen. ⁓ And yeah, it went off without a hitch. It was awesome.

alexjlevy (14:46)

Yeah, was super, super sick.

Mat Vogels (14:47)

It means it's good luck.

It's like raining on a wedding day type of thing.

alexjlevy (14:51)

yeah, incidentally by the way, we have another thing that kind of goes between the two companies, which is ⁓ one of the early models that Atmo did was to create a hyper resolution ⁓ weather model for San Francisco. So we'll send you the link to that if you want to show it to folks. But basically a 300 meter by 300 meter resolution model, which is roughly 100 times higher ⁓ resolution than the previous best over that area. And so that's used by a lot of sailors, but also people that launch

know, balloons and stuff like that in the Bay Area. yeah.

Austin Tindle (15:22)

Yep.

Yeah, I had a lunch this morning, and the first thing we did was check Atmo. Yeah.

alexjlevy (15:27)

Come on, right on, I'd like to hear that, dude.

Mat Vogels (15:29)

So good.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (15:30)

I need to do that too because we just launched

some balloons yesterday. Actually, on Monday, I'm sorry, so two days ago. And the wind forecasts were totally off. so, yeah, wind speed is the enemy of any balloonist. So ⁓ something good to know.

Austin Tindle (15:38)

Yeah, we scrubbed our lunch from a couple days ago for that reason.

Mat Vogels (15:38)

⁓ there you go.

Yeah.

Maybe that's kind of a

perfect little segue into why balloons in general. That was one of the questions that we had in there. I feel like the weather itself, the thing you're trying to measure is your greatest enemy in working with balloons in some cases or not. Could you, maybe Andrew starting with you, why balloons specifically? Why not some other form, be it drone or robot or something to do that task?

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (16:10)

Sure, sure. mean, I the main thing is cost. ⁓ So there's a lot of academic papers have proposed to deploy stratospheric aerosol injection at scale. You either need purpose-built jets that can actually reach the stratosphere because current commercial airliners only go about 30,000 40,000 feet. Even some private jets maybe can reach about 40,000 feet. The only really ⁓ known jets that can fly that high are like the U-2 spy plane, which is around 60,000 feet.

And so that payload is very small. We need to be injecting roughly anywhere from 1 million to 10 million tons of sulfur dioxide per year to get the cooling that we need. It sounds like a lot, but it's actually not. We roughly currently emit about 70 million tons of sulfur dioxide in the air that we breathe in the troposphere. Back in 1979, which was peak Si2 emissions, we used to emit about 130 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the troposphere.

And so we've cut down those emissions, but that's actually subsequently formed at the planet. And so the reason why we use balloons is because one, the cost of itself, but it's fairly scalable. You guys might know, the other guys can check me on this, but NASA launches balloons that have payload capacities about 8,000 pounds, which is roughly like 3.6 tons. So think of like three Toyota Yaris's.

Essentially can be lifted up into the sky. These balloons are really really big. There's a size of like football stadiums ⁓ But those those are the types of balloons that we want to work up to not specifically those those types of balloons But have a payload about one ton of ⁓ SO2 in them Which can offset actually a million tons of CO2 for a year. So ⁓ That's that's the kind of leverage that we're working with here because one gram of SO2 in the stratosphere offsets the warming effect of one ton of CO2 and so

Mat Vogels (17:42)

Holy cow.

alexjlevy (17:55)

Good

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (18:04)

Another thing that's kind of different from us and ⁓ Austin is that our balloons only have to have a flight time of roughly like three to six hours. So because we're just in and out of the stratosphere, we just need to deploy and then come right back down. Austin needs to fly anywhere from 30 to 60 days or even longer. I guess that's more advantageous for you ⁓ because of the use case of the mission. ⁓

That's the big difference. We're more of a single use versus Austin's trying to be more persistent.

Mat Vogels (18:35)

know. Awesome. Yeah, kind of the same question. Specifically on on the balloon side. My my thought was that because you're in the air for so long, you're not going to put a drone in the air, you're not going to be able to do that. Yeah, balloons probably being a huge advantage on your side.

alexjlevy (18:36)

So yeah, really.

Austin Tindle (18:50)

Yeah, mean, the advantage, mean, like you're saying, it's pretty hard to keep a drone up for a meaningful length of time, especially if you want to do interesting data collection with them. So there are lots of really cool companies, actually a few YC companies too, that are working on solar powered high altitude, ⁓ like aircraft type systems. But it's actually a much, much harder problem. Balloons, you fly for free, essentially, right? Like you don't have to, there's no power.

or energy that you have to put into the system in order to keep it airborne. You're just relying on the lifting gas. And so it actually is a really good platform for doing long duration work ⁓ on smaller power budgets. for us, it's also a cost thing. So similar to Andrew, our goal is to have tens of thousands of these systems all around the world.

to make that feasible, especially at the early stage, it's sort of startup scale. Each system has to be fairly low cost. so using the balloon as the platform really, really helps us be able to achieve that scale of not needing billions of dollars. ⁓ We could do it with millions of dollars. And so that's kind of why balloons for us.

Mat Vogels (20:09)

Yeah.

Austin Tindle (20:13)

And I think actually even Alex, might've been, this is what might've been what you were interjecting with, but Apple has ballooned heritage as well with that.

alexjlevy (20:20)

We do. ⁓ That's quite true. ⁓

Atmo's co-founder and CTO, Johan Mate, was one of the ⁓ early and critical employees on Google's Project Loon. So he went around the world launching these balloons and even developing preliminary machine learning models for the weather, even far before the founding of Atmo. So it seems like all cool stuff is apparently coming from balloon guys. ⁓

Mat Vogels (20:30)

Hmm

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (20:30)

nice.

Mat Vogels (20:47)

love

alexjlevy (20:47)

Well,

Mat Vogels (20:47)

it.

alexjlevy (20:47)

and actually the attributes that Austin was mentioning are one of the reasons why we're very, very excited, which is we're forming an alliance between the two companies, between Sorcerer and Atmo. And we've got a bunch of really exciting things planned that we'd be happy to tell you about.

Mat Vogels (20:59)

Love it.

Let's do it, roll into it. You can't tease us like that, leave it out there.

Austin Tindle (21:04)

Yeah, exclusive. You're going to hear it here first.

alexjlevy (21:05)

Okay.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (21:06)

Yeah, let's hear it.

alexjlevy (21:07)

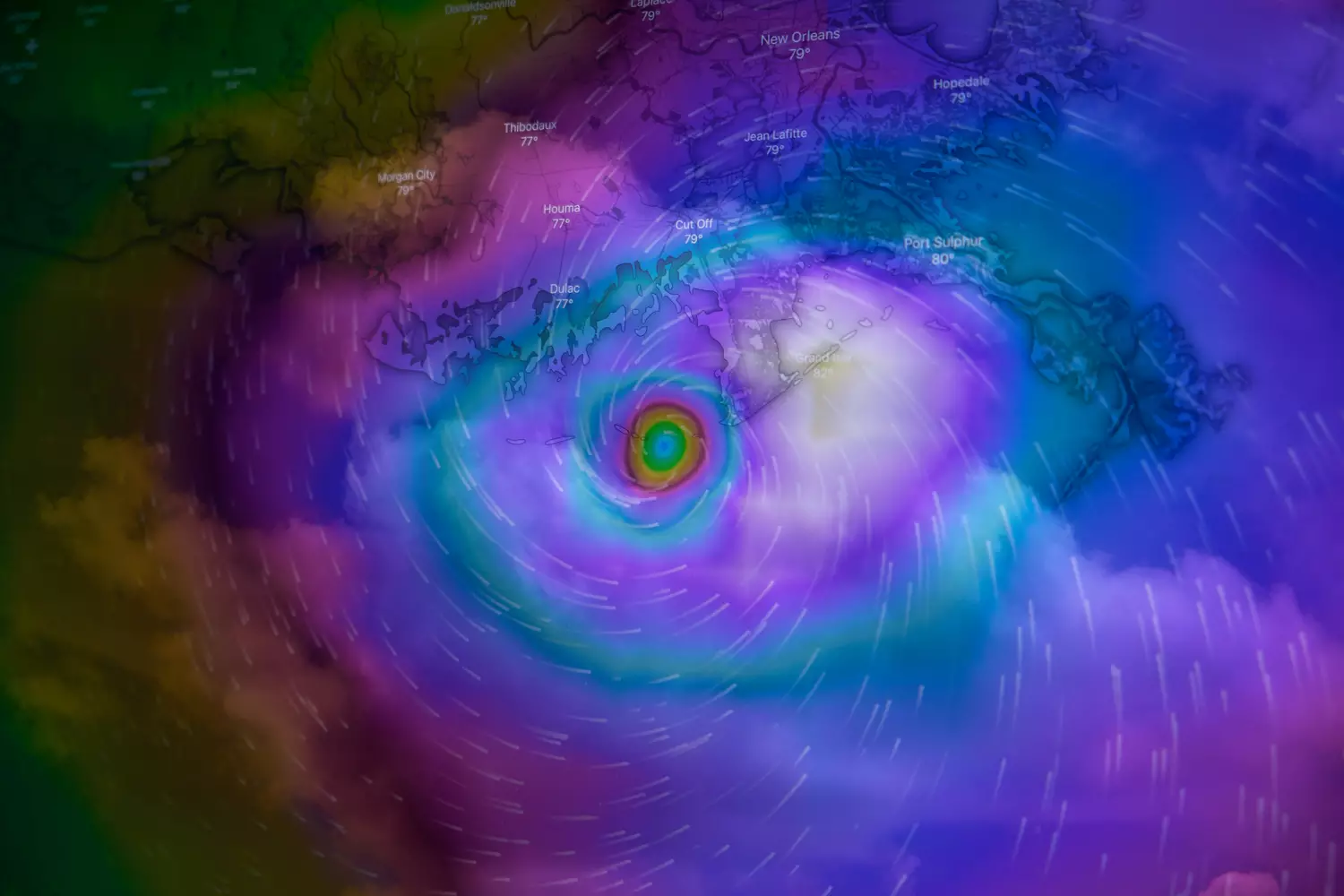

Okay, cool. Well, listen, so at a high level, we got three things that we're kicking off together. The first is ⁓ we've decided that we're going to go launch balloons ⁓ into this hurricane season. And so we're going to take Sorcerer balloons and we're going to deploy them in the Atlantic coast, the Gulf region, and even if we can, further, further out into the ocean, in the parts of the ocean, where a lot of these systems begin to form, where you have proto-hurricanes that then turn into the ones that eventually...

come to the United States. So we're going to use that to boost the performance of, you know, Atmo AI models that are making predictions for those hurricanes in the season. The second is we're going to be working together on doing ⁓ co-sales and projects around the world together. know, Atmo is very fortunate to have a bunch of these great relationships like DoD, Sovereign Nations, great private enterprises and so forth. And we think a lot of those folks will have a great interest in adding on to that.

Sorcerer services and products. And so that's something that we want to make available and vice versa. Sorcerer has some extraordinary customers and partners that Atmo doesn't. And so they may have the option to bring Atmo Forecast into that. And then finally, overall, we're going to undertake ⁓ experimentation to determine how much better we can make AI weather models through the use of the data that Austin and the team are collecting.

So it's a really great multi-dimensional ⁓ alliance and I think it's gonna really kick some ass in the coming years. So I'm really excited to do it with you, Austin.

Austin Tindle (22:36)

Yeah, we're super stoked. so actually all three of Sources' co-founders are from Florida originally and like better predicting hurricane track accuracy and being able to better mitigate sort of the impact of severe storms like hurricanes specifically. It was like a huge driving factor for us starting the company to begin with. And so yeah, this has been a goal of ours is to really dig into hurricane.

forecasting specifically and we're really excited about this partnership and the impact that we hope to have there. Yeah, my family actually, all of our family actually, all the co-founding, co-founders parents still live in Florida. So we're back and forth quite a bit. I was actually there for Ian in Fort Myer. That's where my parents live. So yeah, it's just super close to home and we're, yeah, we're really, really excited.

alexjlevy (23:27)

Well, know man, when we go out there, we'll gotta go do some family dinners with your folks. And dodge some hurricanes, hopefully.

Austin Tindle (23:32)

Yeah, absolutely. That would be a blast.

Mat Vogels (23:36)

Yeah, well, you could use a demo to predict them well in advance to hopefully mitigate some of that. You'll know exactly the perfect time to go out there.

alexjlevy (23:42)

Yeah.

Austin Tindle (23:42)

That's the goal.

alexjlevy (23:44)

Yeah, that's exactly right. Yeah. Yeah. We've had some work in Florida for some, for some time. We've been doing space launch forecasting at Cape Canaveral. ⁓ And so that was, you know, sort of a major first foray into Florida. In fact, I do believe ⁓ that one of the major hurricanes last year passed through the forecast zone that we set up around Cape Canaveral. And just watching it come through the model is just absolutely wild. The intensities, the wind speed, the structure and so forth.

Mat Vogels (23:50)

That's what I was gonna ask, yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (23:52)

That's cool.

Austin Tindle (24:05)

cool.

alexjlevy (24:10)

Anyway, yeah, Austin, glad we're doing this. It's gonna be pretty cool. And then Matt, maybe we'll come back in a year and we'll let you know what we got done.

Mat Vogels (24:16)

Yeah,

I love it.

Yeah, we'll definitely do part twos of a lot of these episodes because there's so much changing, which kind of brings me to a topic I want to make sure that we cover is this idea of changing weather patterns over the course of the years. And Alex, you I spoke a little bit earlier, but the like, could you share a little bit historically of maybe what you're seeing and what the data is telling us and kind of changing. then that kind of leads obviously into what you're doing, Andrew, and helping us hopefully prevent some of these changes happening so drastically. But maybe Alex, starting with you, can you give a high level overview of maybe what the data is telling us on changing weather

patterns and where and how drastic or anything that you can shed light on there.

alexjlevy (24:52)

What the data is telling us is we're entering a higher variance world, a world where the tails of the distribution get more extreme and more populated. Things that were to any end of any spectra of variables are getting stronger and more frequent. And so we see a recent example of this in Southeast Asia. This last typhoon season was extremely intense and particularly intense for the Philippines, this country that we're so focused on. ⁓

unbelievably there was a 27 day period in which six typhoons came through one country, the Philippines, ⁓ which as far as we've been able to tell in records going back to the 1950s is unprecedented. So if you think about it, that's like a typhoon, like one day, two day, three days, next typhoon, one day, two day, three day, four day, next typhoon, just like that. Imagine just being on the ground and having that happen. ⁓ Those types of things are getting more frequent. Another thing that...

seems to be in the data is that extreme rain and flooding is getting more frequent, particularly in places that weren't prone to it before. So if you cast your mind back a few years, you'll remember that there were some pretty stunning floods, for example, in very scenic parts of Western Europe, like in Belgium and Switzerland and parts of Germany, places, you you've got these sort of quaint townships that are traditionally very, very calm in terms of weather. And they're having these sort of massive flooding events that look like a totally other region of the world.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (26:03)

Spain.

alexjlevy (26:14)

So the frequency of these extreme events appears to be going up. And also, as the atmosphere warms, its capacity to carry moisture changes. And that has a big effect on moisture dynamics. There's this very crude analogy of it being like a sponge. And the hotter it is, the more that sponge can hold. And so ultimately, there's a continuity, a conservation of that mass. And it eventually does come down somewhere.

Austin Tindle (26:36)

Just to add to that before Andrew tells us how he's going to fix it, ⁓ the problem of more extreme weather is exacerbated by the fact that weather infrastructure has stayed pretty stagnant across the world. And in places that are most heavily impacted or most at risk for the increase in ⁓ climate change-induced extreme weather are in parts of the world where the infrastructure is terrible. ⁓

and we don't collect the data that we need to even do the forecasting to begin with. We work really closely with the government of El Salvador, and it was one of our really early partners. And one of the striking things that they shared with us ⁓ at the outset was that they'll have a one-day forecast, and that one-day forecast will be about the same accuracy as a seven-day forecast in Florida, which geographically not that far away. ⁓ But a lot of that comes down to the

El Salvador is a country that's kind of on both sides, know, big bodies of water. And the infrastructure isn't there to collect the data they need to do, then, you know, provide sort of their country, their, you know, their economy, et cetera, with, you know, accurate forecasts. And so the extremes are getting more extreme and the infrastructure is, I mean, if anything, it's degrading, you know, with what we've seen in the US recently as one example, lots of, you weather infrastructure.

that's shutting down or, you know, we've got less data overall, but.

Mat Vogels (28:01)

Yeah.

alexjlevy (28:03)

Right

on. Yeah, no, Austin's 100 % correct. 100 % correct. Yeah, there's been this dynamic for ages in meteorology of the best and the rest. There's this club of nations that's able to spend billions and or even tens of billions a year and they get, you know, the top of the line forecasts available and then you have the vast majority of other countries. And that's not right in a world where the burden of these events falls disproportionately on the rest.

Mat Vogels (28:05)

And I know that I, yeah.

alexjlevy (28:27)

And so in a combination of cheaper, better sensing, cheaper, better weather models, there's a possibility to flip that dynamic and actually have some of these countries leapfrog and have better models and better forecasts than even the really wealthy counterpart nations. So that's going to be amazing to see. And that hasn't happened really in the history of meteorology before.

Mat Vogels (28:48)

Could you, could you share actually quickly on maybe is from a history lesson. What is like an accurate forecast historically kind of look like? I and even sharing it today and then maybe projecting forward of what you're going to be able to do in, the next decade or so where today is it pretty accurate like across the globe or with good models to predict.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (28:48)

you

Mat Vogels (29:06)

I live in Colorado and I feel like the weather is never what they say and obviously it's tough. So just from like a normal person thinking about the weather, why is it that I've never seen an accurate weather forecast? ⁓ And obviously we're changing some of that, but maybe just from like a brief history lesson there.

alexjlevy (29:22)

Well, if you think it's bad now, imagine how was in the 50s.

Mat Vogels (29:25)

That's what I'm worried about. Yeah, so is it whether predictions

gonna like just come back? It's gonna be the same, but it'll just ⁓

alexjlevy (29:30)

No, mean, look, in

a way, we're in a paradise for meteorology compared to where humanity was in the 50s and 60s. mean, numerical weather prediction, which is the term of art for computerized weather forecasting, a certain technique. It was like the second program ever run on the ENIAC, the first digital computer. So the first was ballistic trajectory calculations, so just where's artillery going to land? And the second was a very crude form of meteorology. So this is like one of the oldest programs that humanity runs. And even today, we dedicate something like

Mat Vogels (29:35)

Mm-hmm

course.

alexjlevy (30:00)

half of the world's largest supercomputers, part-time or full-time to atmospheric simulations. So it's like a huge, huge, huge consumer of all our compute in the world, totally on par with our use of compute for AI. In rough terms, we have seen in the last couple of decades, forecasts get about ⁓ a day ⁓ better per decade, I should say. So what that means is between, yeah, so between, let's say, the 70s and 2000s,

Mat Vogels (30:22)

wow.

alexjlevy (30:27)

What would have been the quality at let's say a day three forecast becomes the quality at a day six forecast. So roughly we can see roughly a day further per decade. But what's been I think disappointing to people is that the classical pre-AI method has been tailing off in improvements. So it's been asymptoting. So the best forecast in the world, many of them have only been improving about one to 2 % per year now for the last little while. And that was starting to get this disheartening.

place where people thought, oh man, we're going to kind of, this is it, like we reached the end of line for this. And then along comes stuff like, know, what, what, you know, a sorcerer and an Atmo are doing, showing actually this new radical curve that's able to jump it back up. so some of these new AI weather models have seen gains in under a year of 20, 30, 40 % or more of reduction in error. So what that's allowed us to do is that equal accuracy sometimes extends forecasts by as much as, you know, three to seven days.

while maintaining what would have been the same curve of accuracy before. ⁓ So that's the good news. The bad news is that's going to take a little while to make its way particularly to you ⁓ in the United States because actually of the countries, one of the very few that does not have a national AI weather model yet is the United States. So even though we've got the best companies in the world that have invented this technique, we've actually much more readily brought it to the military or brought it to foreign countries than we've actually brought it to the National Weather Service.

Austin Tindle (31:42)

Thank you.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (31:43)

Interesting.

alexjlevy (31:54)

So keep an eye on that. Well, know, ⁓ politics and government is complicated, but I think the simple answer is it's very hard to turn an aircraft carrier. And so, you know, the US National Weather Service has had the benefit of enormous funding and has done amazing work over many decades. But to turn that ship of thousands of people is much harder than to turn the ship of, let's say, a country like

Mat Vogels (31:54)

Why is that?

Austin Tindle (31:55)

Thank

Mat Vogels (31:55)

Why is that?

What's the reason why?

Okay.

alexjlevy (32:19)

a country in Latin America or in Southeast Asia where the teams are smaller, they're more nimble, they're more highly motivated for change because of where they are kind of in the rankings. ⁓ So, know, but it's coming. I mean, I think everybody understands this is gonna be the future. And so hopefully the sooner we can get it to you, better. And then it can show up in your app and you can have a better day in Colorado.

Austin Tindle (32:40)

So.

Mat Vogels (32:41)

Yes, hopefully so. ⁓ I know Alex that you have to go a little bit earlier here. I wanna give you a little bit of a platform before you go to just share any CTAs, hiring, announcements. Obviously you shared a big one here with Sorcerer in Austin. ⁓ Anything else that you wanna share before you have to get any CTAs for folks.

alexjlevy (33:01)

Sure, just two. First of all, we're super, super excited to be in a new alliance with Sorcerer. We have followed this company since day one. Huge admirers. We're there to help launch some of the, I guess, balloon number eight. And we're going to go out there and launch a lot more balloons together, and we're going to use this to make better forecasts. So we're super psyched, and I'm very grateful to Austin and the team for the partnership. And second, Atmo's primary customers really are heads of state, people that run entire military sovereign nations. So if anybody's listening to this,

Austin Tindle (33:12)

You

alexjlevy (33:30)

from a ⁓ presidential palace, a parliament, or sort of any of the halls of power, and you don't yet have AI meteorology where you're sitting, please reach out to team at atmo.ai because we'd love to come to your country, military base, wherever you may be seeing this from. So bring us those high-level contacts and we'll get you good forecasts.

Austin Tindle (33:34)

you

Mat Vogels (33:35)

Hahaha

Love it. Thank you, Alex, for jumping on. Pleasure to have you. We'll have you on again. We'll do some more topics on the weather. We could have talked probably for another couple hours on this stuff. ⁓ But yeah, thank you again for coming on.

alexjlevy (34:06)

Right on, go make sunsets and go sorcerer and go pirates only.

Austin Tindle (34:09)

Thank

Mat Vogels (34:11)

There we go, appreciate it. See you Alex.

alexjlevy (34:12)

See ya.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (34:14)

See you, Alex.

Mat Vogels (34:15)

Andrew, so we just spoke a little bit over the last 10, 15 minutes on the weather patterns, the changing, the more drastic pieces.

Can you talk a little bit about what it is that you're doing, how you're combating that? I know you obviously gave a little bit of a rundown of how you're changing that, but ⁓ maybe share more specifically what you're envisioning over the next five years, 10 years with what you're doing, maybe what other technologies are doing and how we can hopefully retroactively help with these things or at least mitigate some of these damages. The floor is yours.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (34:44)

Thank you, thank you. And so, I mean, we could just keep going on the conversation that Alex was talking about and what Austin's trying to do. ⁓ know, ⁓ Alex is interpreting the data and giving the best ground truth data interpreted to these heads of state so they can plan accordingly. And then Austin's actually remote sensing up there ⁓ and actually gathering that data. ⁓ I think that's the big thing that is really gonna make a difference. ⁓ And we're trying to do the same.

We know that historically, stratovolcanoes, specifically stratovolcanoes, so those are the types of volcanoes that you probably grew up in grade school making, we had a paper machine and stuff. The most famous one is Mount Fuji in Japan, but that's what a stratovolcano is, the classic shape. ⁓ And so we knew that it actually cooled down the planet because we had satellite data out there, or satellite infrastructure, detecting those volcanic eruptions and then measuring what is called radiative forcing, meaning how much energy we're absorbing versus reflecting away.

Because sulfate aerosols, what they do is they actually reflect energy. And greenhouse gases like ⁓ CO2, carbon dioxide and methane actually absorb the sunlight, keep the the planet hot. And so with this data, ⁓ as we knew that it worked, and so, you know, as we go along in the next five to 10 years, we're going to be continually increasing our dosage of sulfur dioxide to get closer and closer to that pinnateable level of 20 million tons.

⁓ And I don't think we'll have to go that high, but as we're going, we're going to be introducing in situ data, situ aerosols. So then ⁓ companies like Austin ⁓ at Sorcerer, as well as Alex can interpret that and put those into their models and have better predictions of, hey, look, I see that over here in the Philippines is getting a little bit too hot. Maybe we have to do something over there and have some kind of intervention to cool that system down so we can just prevent hurricanes from happening in the first place. ⁓ And so

Austin Tindle (36:24)

you

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (36:40)

I mean, just like us three all just working together just sounds really interesting. For the next 10 years, like we could be that trifecta. Yeah, exactly. Exactly. And so, mean, Austin, you want to say something?

Mat Vogels (36:47)

Powers combined.

Austin Tindle (36:49)

Yeah.

Yeah, I was going to say it's super interesting because the type of ⁓ geoengineering and weather modification, if you will, that makes sunsets work. It's fairly well understood. And like you saying, Andrew, the studies go back to the 60s and 70s. ⁓ But ⁓ looking bigger, when you're talking about eventually really wanting to control or have big influence on what the weather's doing at a global scale.

beyond just ⁓ stratosphere cooling, aerosol injection, we don't have the accuracy needed in our forecasts globally to even have that conversation yet. I know it's really interesting. There's been some hype recently on lot of weather modification and other companies and projects and groups, and they're all working on really cool stuff. But almost the first step is that you need to have

much more accurate global weather forecasting. ⁓ And that's what's really, really exciting. Thanks. Yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (37:54)

Exactly. What's the baseline? Yeah, yeah.

We know directionally that sulfate aerosols cool down the planet, and we know that CO2 increases global temperatures. And so now we need to know exactly how much. And so instrumentations that Austin flies would be critical in that piece as we move forward in scaling up our deployments. I think that's the most exciting thing about this. I mean, we were thinking maybe we need to use better satellites, because there are satellites like there's the Tropomi

Austin Tindle (38:02)

Mm-hmm.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (38:22)

that's on the Sentinel-5, which is run by the European Space Agency, that can detect volcanic eruptions and radiative forcing, meaning, again, how much energy we're absorbing versus reflecting away. But knowing, putting up other different sensors, a constellation of these sensors using balloons to detect the sulfate aerosols as well as radiative forcing would be huge. And that's just the infrared camera, by the way. So it's a super cheap sensor. It's not something very exotic. It's just...

Austin Tindle (38:46)

Yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (38:51)

Measuring again, watts per square meter is the unit of measurement.

Austin Tindle (38:54)

Yeah, and I think it's like, there are always, it's always going to be sort of a sensor fusion approach, if you will. Like we need satellites, we need more ground infrastructure, we need buoys, we need sensors on airplanes. ⁓ But really what it comes down to is like, we're moving into an era where we can do some really, really cool stuff with weather prediction on the back of, you know, AI revolution that's happening, that's driving costs just down like to, you know, it's sort of unprecedented cost reduction.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (39:16)

Exactly.

Austin Tindle (39:23)

technology bringing unprecedented cost reduction. And we still don't know all of the impacts that reduction is going to have. ⁓ We're just really scratching the surface of, we're doing sort of the boring things first. We're making the models that we have a little bit better or a lot better in many cases, but we haven't started, there are all these new opportunities that are available from, if something costs, if I can run something on my MacBook versus a supercomputer, right? Like that opens up,

hyper local forecasting and for specific variables and specific use cases. And yeah, it's a really exciting time to be working on kind of in this space. Yeah, I think the next 10 years is going to be very interesting what we're able to accomplish kind of on the back of all this tech.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (40:10)

Yeah, it's just the feedback loops I think is the most important thing is just they're getting tighter and tighter. ⁓ And so like, hey, we're gonna put this much sulfate aerosols up. ⁓ Austin's balloons are gonna sense it plus some sensor fusion with some satellite data as well. And then that's gonna be all that data is gonna be plugged into Atmos. And then we can get better and better at this because again, Mother Nature did a good job of showing that it works. ⁓ Now it's our job to actually then say, okay, how can we make this better? How can we do this?

in a more controlled manner because volcanoes are pretty violent. ⁓ the reason why too is also that they also put up other stuff too. They put up sulfur as well as carbon dioxide. There's even some volcanoes that shoot up gold. There's a volcano in the Arctic that actually shoots about $6,000 worth of gold dust per day. ⁓ so it's like, yeah. I don't know what the last time I the article was like.

Mat Vogels (40:50)

Yeah.

wow.

Austin Tindle (41:02)

That's a great metric.

Mat Vogels (41:04)

Wow.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (41:09)

reference was like, I think pre-pandemic. So, you know, gold prices have gone up. So maybe it's like $10,000 now, it's like volcanoes are very fascinating and we can look to mother nature to really help us, you know, get better at essentially, you know, one, predicting the weather, but then also how to then after predicting the weather, what can we do with it? Because we know how to heat it up. It's just add more CO2.

Austin Tindle (41:34)

Yeah. So Andrew, I'm curious because like your long-term vision for Make Sunsets, the, will you always be deploying via balloons or is the idea that you'll move to a new paradigm or is it like you're trying, you know, the end goal is to get enough buy-in from, you know, from other groups. know the figure is like 10 to 15 billion a year or something that you need to do this via like some 47s essentially. But I'm super curious about that.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (41:59)

Yeah,

Yeah, yeah. what you're touching upon is a scale up. We can get pretty far with balloons. Just to give you an example, the balloons that the next milestone we're working up to is that one ton payload. Again, that offsets a million tons of CO2 per year. To offset ExxonMobil's scope one and scope two emissions, meaning that's like direct emissions. That's not like them selling gas and then ⁓ burning that gas. Then that's considered scope three.

but direct emissions that ExxonMobil produces. They emit roughly around 100 million tons of CO2 per year equivalent. And so ⁓ to essentially offset that warming that is caused is 100 balloons. So that's not a lot. ⁓ That's how powerful this technology is. So you can get pretty far ⁓ to give you even another difference of scale and leverage ⁓ to offset. ⁓

global emissions, roughly the last number I looked at was about 37 billion tons of CO2 was emitted in the previous year. So again, that sounds like a lot, but essentially we would need roughly 37,000 balloons to offset that warming for a year. And so it's like 37 billion tons of CO2, right? And you only need 37,000 balloons, one ton balloons. That's not crazy, like JFK.

Mat Vogels (43:16)

That's not crazy. Yeah, when you put that math together, it's not crazy.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (43:19)

JFK does, I think, roughly around 200,000 flights per year. ⁓ And again, we're not flying planes here. We're flying balloons. And so they're pretty simple. But to touch on what Austin's saying, how do you scale it from there? We're not married to any certain type of delivery vehicle. For example, actually, one of our investors is an early employee of a supersonic company, supersonic jet company. And so whenever that supersonic jet company is ready to start flying certain people or

payloads, we could just strap a device to one of their wings and deploy that way at scale. ⁓

Mat Vogels (43:54)

Would that work at that altitude

though, or is there like an altitude requirement that they would have to hit?

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (43:58)

Exactly, exactly. that's why it's a supersonic jet company. It's because, characteristically, they have to fly higher to get a better fuel economy. Because if you fly lower at supersonic speeds, ⁓ the whole airframe actually heats up. ⁓ And that becomes dangerous for the plane. So they have to fly higher where the actual wind molecules are less dense. So they just go higher. ⁓ But there's a lot of different ways to do this. ⁓

Mat Vogels (44:02)

Yeah, so it's higher up. Yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (44:26)

to cool down the planet. Ultimately, think the holy grail is space mirrors. So putting a constellation of solar sails at the Lagrange point. so eventually, I think we will get there ⁓ once launch costs to get things into actual space becomes less and less. And I see that world happening. But right now, it's just too expensive. It's in the trillions of dollars. Plus, we don't have the material science done yet.

Austin Tindle (44:38)

Cool.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (44:54)

This is essentially a stopgap solution. But ⁓ I want to stop using sulfate aerosols as soon as possible. It's not the best thing to put up in the atmosphere. There's other candidates of molecules that you can use as well. And so those are just not being actively explored because it's such an underserved market. There's not a lot of data around this. And so what we're doing is going with what we know, ⁓ is that naturally occurring substance, sulfur dioxide, that is being emitted right now. ⁓

Again, people freak out saying, hey, wait a minute, sulfur dioxide, that's acid rain. But listen, again, we emit 70 million tons of this stuff right now into the air that we breathe. If we actually stopped all those SO2 emissions tomorrow, we would live in a 1.9C world. The current emissions that we're putting in the troposphere is currently cooling the planet by 0.57 degrees Celsius. So that's a lot of cooling. ⁓ But we're just doing it in the wrong place.

Austin Tindle (45:22)

to do.

Mat Vogels (45:47)

It is.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (45:51)

We're doing it the wrong place and too low. If you do it in the stratosphere, there's this thing called resonance time, meaning how long an aerosol actually lasts in a particular part of the atmosphere. In the troposphere, aka the air that we breathe, only lasts roughly around 10 days and then it falls out due to gravity or rain. But if you do it in the troposphere, ⁓ none of the, we're above the clouds, we're above the rain clouds. And so it can actually, if you inject it in the right place, ⁓ which is close to the ozone layer,

it can roughly last from one to three years. So one, you have to apply less, but then also the winds go super fast. It's called the Brudopsin circulation of how we actually transport these aerosols all throughout the earth. ⁓ Can actually evenly distribute ⁓ the aerosol very, very, very ⁓ evenly, which then actually cools down the entire plant. So that's why Pinatubo was able to actually cool the entire plant by 0.5 degrees Celsius. Hungatunga was a little bit more southern.

So it only covered the southern hemisphere. But essentially, the academic papers and modeling has said, you need roughly around 6 to 12 different injection points north and south of the equator, and you can get pretty good distribution of aerosol itself. And so having roughly these automated balloon launching robots that can send up these really, really monster balloons dotted around these island nations like the Philippines, like actively deploying, and then also, you

Mat Vogels (47:07)

Yeah.

Austin Tindle (47:14)

So, good luck.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (47:18)

connected to maybe Atmos's API for AI saying, OK, looks like there's a hot spy here. We need to launch a little bit more balloons. And Austin's balloons are sensing all this stuff. We can just have this essentially thermostat. We can just start controlling, saying, It is. It is. is. I I want to live in a world where everyone has a thermostat on their wall for indoors. Why not have one for outdoors? ⁓ I mean, we can control in our cars.

Mat Vogels (47:32)

I was just gonna ask, it's almost like having an air conditioning unit built into the planet.

Austin Tindle (47:34)

Yeah.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (47:48)

per seat, right? We have zone cooling, zone heating in our cars, in an individual level. Why can't we do that for

Mat Vogels (47:56)

in a way we're almost doing what seems like the earth's natural way of cooling the planet. And we're, you know, the feedback that we even got leading up to this episode, I'm sure that you get a lot is we shouldn't be doing that. It's like an act of God. We shouldn't be the ones that are trying to control the thermostat of our planet. Like that's, that's out of our control. Can you talk a little bit about maybe what the consequences are, if there are any, or, ⁓ obviously you're probably getting a lot of

pushback on doing this and people are taking pictures on Instagram of weird clouds in the sky and blaming you for it. Can you talk a little bit about that and why that's maybe not the case and stomp out some of those things?

Austin Tindle (48:29)

Thanks

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (48:32)

Totally, totally. think the high level is it's the dose that makes the poison, right? We're not trying to, you know, I think everyone here probably drank a cup of coffee before they jumped on the pod to be a little bit more chipper. Hey, and now you're an active member of society. But if you drink 100 cups in less than an hour, you will die. It's not good for you to have that much caffeine in your blood. We're not saying we need to put 100 cups of coffee into the stratosphere.

we're saying less than a drop of coffee. Like that's how little amount of sulfur dioxide we need. And so when people get really apprehensive about stratospheric aerosol injection, they don't understand the scale that we need. And so a lot of the academic papers have kind of caused this fear mongering because ⁓ what's been happening is the reason why, what academia does is when they write these papers, they have to use the most extreme use cases.

Because otherwise if they do something conservative and saying hey, it actually can relatively cool down the planet It doesn't get the headlines that they need to get then the funding that they need to continue to pursue this research and so there's this weird cycle that's happening right now in academia with stratospheric aerosol injection where they'll have to write these very extreme types of scenarios of putting like X more times of sulfur dioxide than we need to then push the models and saying okay

This is what will happen if we do that. ⁓ What unfortunately happens is that the mainstream media then picks up on that and sees that as literally as like rage bait, as click bait, as saying, hey, this is gonna affect monsoon patterns in India by 5 % if we do X amount. They never disclose how much amounts of SO2 that you need for that bad thing to happen, but it's these very extreme use cases and scenarios to do so. And so there's that mismatch of like, okay, everyone focuses on the bad things.

but they don't realize we need very, very little amount of that in order to get the intended cooling that we need to cool down the

Mat Vogels (50:33)

Now, what other, places can folks go if they're skeptical right now, even listening to this, where can they go learn more about this type of content and better educate themselves maybe on some of this.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (50:44)

Thank you. That's a great way to ⁓ plug into the segue. ⁓ Follow us on Twitter. ⁓ We are at make sunsets is our handle and we actually share the papers as well as how we interpret this stuff. ⁓ Also our website. ⁓ We're doing this open out in the open. I think one thing that we did strategically was that on our blog, we share every single month how much money we have in the bank, what our revenue was, what we succeeded and failed at.

what we're working on next month and ⁓ we do that monthly. And so this is actually our investor update. We share this monthly with our investors as well as our customers, our haters and our SAI curious. And so it's something where this is gonna affect us, affect everybody. And so this should be a thing that everyone knows about. And if you think that you want to help us, you can go to our website and actually buy some cooling credits. That's the product that we sell.

Austin Tindle (51:23)

See you.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (51:39)

⁓ because one cooling credit offsets the warming effect of one ton of CO2. And so the average American roughly emits about 16 tons of CO2 per year. And so you can go on our website. It's a very small amount of money in order to make an impact.

Mat Vogels (51:54)

Love that. Any other CTA, anything ⁓ that you want to drive traffic towards or for?

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (52:00)

I don't think so. think it's really, yeah, check out our website and follow us on Twitter because those are the places where we're most active. Read those academic papers, but always have that lens. whenever you read, when you do read these, like, because there's a lot of articles now coming around about stratospheric aerosol injection. was the UK government just kicked off like a, I think it was $65 million worth of solar radiation management research.

Mat Vogels (52:26)

research.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (52:30)

Mostly it's around modeling, no deployment projects. Again, we're the only ones in the world currently deploying any type of sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere. closely follow those things, but always have a lens of how much does that bad thing need to happen in order for it to actually happen. And once you realize it's the dose, again, that makes the poison, then you'll look at this in a different light.

Mat Vogels (52:58)

know, I strongly recommend it. I mean, that's where I send a lot of folks whenever they ask you about it, because I'm very interested in this space. I love make sunsets and have shared it with a lot of people. And I think you're doing both really well and that you're you're doing the thing that you're saying you're doing. But then you're also educating people and keeping it wide open on on the effects and all the reasoning. So it's incredible. I can't recommend checking out your site following you guys enough. ⁓ It's it's a it's a must follow.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (53:24)

Thank you so much.

Mat Vogels (53:26)

All right, Andrew, thank you so much for jumping in. We'll do this again and congrats on everything. Good luck with everything and we'll chat again soon.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (53:34)

Sure, for sure. And hey, Austin, ⁓ tell Max to send some radio songs to us, because we need to do another flight. ⁓

Austin Tindle (53:40)

Yeah. Yeah, were actively, I mean, I'm looking at him build a couple more payloads for, ⁓ we just onboarded two new hardware engineers this week. And so, yeah, we've been in sort of like hiring mode and they're now.

Andrew Song (Make Sunsets) (53:52)

Nice. Amazing.

Training mode,

yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Onboarding, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah, cool. Yeah. All right guys, take care, peace.

Austin Tindle (53:56)

back into, yeah, so yeah, we're, yeah, exactly. Cool, all right, talk soon, Andrew.

Mat Vogels (53:58)

Fundraisers do that to you, yeah.

See you, Andrew.

Austin Tindle (54:05)

See ya.

Mat Vogels (54:07)

So Austin, one of the questions that we had submitted from folks going into this was specifically around the unique advantage that you have at Sorcerer and that before Sorcerer, the oceans were kind of this desert of not being able to read. And as we learned earlier in the episode, so many of these weathered patterns begin in those areas. Can you explain a little bit maybe how you were able to fill that gap and what was being done before Sorcerer to do that?

Austin Tindle (54:26)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, so the weather community ⁓ understands the importance. The ocean really is a, ⁓ it's like half of the system that ultimately causes weather. The ocean is tightly coupled to the atmosphere and we have to have a good understanding of both to really be able to move our forecasting accuracy and skill forward.

Like the weather communities understood that for a long time. we've had, you know, through both the government and private organizations that are aimed specifically at collecting data from the oceans. know, like NOAA will deploy weather buoys. There's another really cool company actually in San Francisco called Sofar. really cool company deploying buoys, both

who is that drift around the ocean and are also anchored. And they're collecting both sea surface data and then underwater data. ⁓ So there is some infrastructure and there are lots of ways that you can collect useful data. But what's been missing and what's been basically impossible to get ⁓ up until now is what's happening at what's called the planetary boundary layer. So that's sort of the lower troposphere down to the surface.

And so that's, you you have to be in the air ⁓ with a sensor to collect that data. Satellites really struggle, or at least the prevailing sort of satellite technology for ⁓ collecting weather data from space really struggles at that layer. ⁓ There, you know, over the oceans, are no, ⁓ you know, there's no real infrastructure, right? So, and to gather data from, know, we're talking about like roughly 5,000 feet up. So from the surface to 5,000 feet in most places.

You have to put something there. You have to put a sensor there. And so you can do that with a drone. But we talked about limitations there before. ⁓ You can do it with airplanes. typically, your airplanes aren't flying at that altitude for long variations of time, especially over the ocean. And so what you're left with is.

Mat Vogels (56:41)

My guess is, it harder

to read? mean, the speed of an airplane too, does that make it a little bit harder to read as well?

Austin Tindle (56:46)

Yeah, the airplane platform introduces some unique challenges that are unique to planes specifically. But actually, the biggest downside or limitation with airplane data is that airplanes typically cruise at a set altitude for most of ⁓ their flight. And they really only descend through the atmosphere. they're collecting. The atmosphere is like cake. There's hundreds of layers that are all important to model distinctly, or at have an understanding of distinctly.

Mat Vogels (57:09)

players.

Austin Tindle (57:15)

And so the really high quality airplane data is actually when they're either launching or landing at an airport because they're kind of sampling all of those different layers. those layers and needing that vertical slice, kind of why balloons have historically been ⁓ sort of the standard ⁓ way and the most high impact way to collect that data. And it's something that just will naturally travel upwards through the atmosphere. They can sample data at each layer. ⁓

And traditional weather balloons, so your single use ⁓ weather balloon that will be launched by your national weather services all over the world, ⁓ about 3,000 of them go up every day. And they're completely single use. They become litter effectively after a couple of hours. And ⁓ just under a million are being launched, or just around a million are being launched every year to collect that data. mean, the scale of the existing balloon infrastructure ⁓

is already pretty massive. And that gives you an idea of how important it is to doing weather forecasting. But obviously, on the ocean, the only way you can launch a balloon is off of a ship, right? Or if you happen to be island. ⁓ It's really hard to put any meaningful infrastructure ⁓ out over the ocean. So with our platform, we can descend to the surface and then continuously sort of side-to-soil-ly operate our balloons out over the water. And we're collecting

thousands of times more data in those regions than any other platform that's been thought up to date. And so that's the advantage. We're filling that really unique gap. And to give you an idea, it's like less than 20 % of the atmosphere is sampled in this way. most of that gap's over oceans. so it's super important data, super high impact.

Mat Vogels (59:02)

That's crazy to me.

Austin Tindle (59:10)

Yeah, we're collecting it in a really cool and unique way.

Mat Vogels (59:14)

I love that. I mean, it's always those things that always get me excited about the future of technology in general is we're also excited about going to space on a previous episode. talked about how space just has a really good PR team behind it. Like we think about like, let's go to Mars and go to it's it sounds so fun and adventurous, but we still have so many things that we can do here on earth. Be it the oceans, the skies.

Austin Tindle (59:25)

Yeah.

Mat Vogels (59:35)

I think that there's, still so much opportunity with that. You already shared some of the unlocks that could happen. there any kind of final unlocks or things that gets you excited about the space in general, weather in general, things that we don't have today that in five to 10 years, because of what you're doing is going to be a new norm and maybe what that looks like.

Austin Tindle (59:54)

Yeah, I think we're seeing very, really clearly that on the algorithmic modeling software side with what's happening with AI and specifically AI for weather forecasting, that we're in an unprecedented era of compute that can be used usefully for modeling the real world. ⁓ And we're still, it'll probably take us 10 years just to figure out all of the implications of the technology that we have today and the advancements that we've made just in the last three or four years. ⁓ But a current

A huge limitation on the other side of things is that the data that's feeding those models as effectively all coming from the same infrastructure that has not meaningfully changed since the 1980s. And that's almost like a dirty secret of a lot of these AI weather modeling operations and companies and programs is that they typically, I mean, they don't typically, they all train on the ⁓ same what's called analysis data. And so this is data that's

basically taken from all the observation types from all over Earth and normalized into a gridded, ⁓ normalized grid of the atmosphere. ⁓ And you kind of need to take that step as a preemptive step before it's useful to a weather model. And that data that goes into that analysis data, the observation of raw sensor data, it's definitely not increasing at the same rate

that the advancements on the compute side are increasing. so I think that what we, hopefully what we see, but what we really need ⁓ is a similar explosion of high quality environmental data. Obviously we're attacking the atmosphere and we're trying to put thousands, tens of thousands of low cost, high impact sensors into the atmosphere. And I think that trend will continue.

component miniaturization is happening. ⁓ There's, I think, going to be, or there has been a lot of movement on the robotic side. A lot of these far-fetched use cases for interesting hardware have been far-fetched because ⁓ a lot of times the software that you need to run them or the software that would make them useful doesn't exist. And now with AI, seeing a lot of that come.

⁓ you know, come into being. And so I'm really excited for the, you know, having sensors out in the real world and collecting data about the real world start to catch up with what we've seen in advancements on the AI side.

Mat Vogels (1:02:33)

It's amazing. AI is eating the world, not just software, but even the weather, which I guess can be software in a lot of ways as well. ⁓ Well, thank you, Austin, so much for staying on a little bit longer as well. Do you have a final CTA you announced that you just raised some funding? ⁓ I'm assuming you're hiring. Is there any last CTAs or things? Where can folks find more about you?

Austin Tindle (1:02:36)

Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah, we're hiring, so you can check out our website at sourcer.earth and see what roles we have open there. Yeah, and similarly, we ⁓ also end up dealing a lot with governments and larger enterprises, ⁓ the DOD as well, if there are those types of folks out there that know they can gain ⁓ a competitive advantage or can

can get an edge with higher quality data in hard to reach areas, and we'd love to talk with them. yeah, otherwise, really, really happy to have been part of Pirates Only and excited for the next one.

Mat Vogels (1:03:36)

Love it. We'll definitely do it again. We're also thinking about doing one-on-one episodes, even kind of what we're doing right now. I think a lot of folks like that one-on-one approach as well, along with the team, but ⁓ we'll definitely schedule another one of these to hear about the progress you've made and ⁓ talk to me about the partnership that you have ⁓ going on as well. So that'll be great. Sweet. Well, thank you, Austin. Have a good rest of your week and we'll chat soon.

Austin Tindle (1:03:57)

Awesome. Yeah, looking forward to it.

Thanks for that. Talk soon.